The bees sit still in their cluster all winter and only heat up the area where they sit and therefore no insulation is needed. The bees sit under the food and the honey thus maintains the same temperature as the outside, whereby the cluster slowly moves upwards as the food runs out.

This is what I thought for a long time, but it has always bothered me that the model has some weaknesses that are difficult to answer, namely:

1. How do the bees get the food down to the brood chamber when the food is generally outside the cluster and is frozen solid?

2. The model requires some form of altruism in the bees, which is unlikely. The mantle bees (the bees that are on the outside) must maintain at least 10 degree C otherwise they will end up in a cold coma and inevitably die. To avoid the mantle bees dying, the bees in the center must somehow know that they must relieve the mantle bees and be willing to do so. In addition, the mantle bees must be able to get into the warm center. Impossible? No, but unlikely.

3. Intuitively, you realize that the colder it gets around the cluster, the more the bees have to work to keep warm. The bees that are on the outer layer have little benefit from the insulation and are forced to produce heat otherwise they will die. Many beekeepers still believe that bees produce less honey the colder it gets, which we will soon see is completely wrong.

It seems illogical that the bee colony chooses a strategy where a large proportion of the bees have to work at the highest level in order to survive, which leads to their likely premature death.

Let’s look at it scientifically instead:

Bee clusters are very effective at surviving a cold environmental because:

The bees are packed tightly together, which creates good insulation

Bees have the ability to ventilate away moisture and CO2

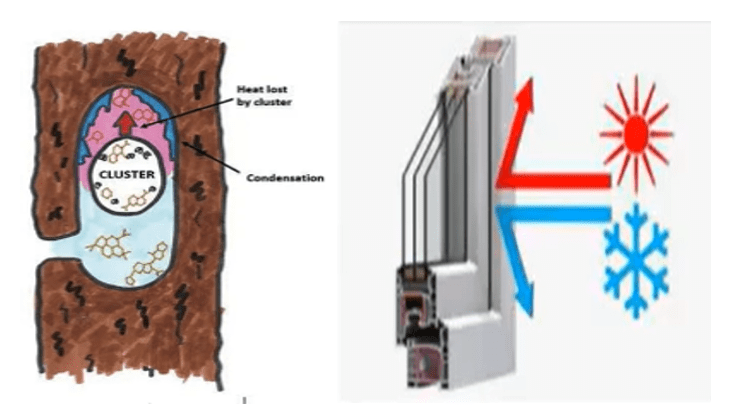

Thanks to this, the bees can keep the environment in the middle of the cluster at a comfortable level for the bees, where the bees’ metabolism is enough to maintain a temperature of 20-25o C (1). However, this comes at a price – the bees that are unlucky enough to end up in the mantle (the outermost layer of the cluster) are worn out – because the mantle bees have to produce enormous amounts of heat (2) to stay above 10 degree C, below which the bees fall into a cold coma and eventually die. In addition to the cold, moisture during the winter is also a big problem for the bees, because moisture causes the bees to lose their insulating ability. I beleive most people understand intuitively that moisture is a problem, but why the moisture occurs and how to avoid it is a bit more complicated.

Dew point

We start with the concept of “dew point” which means the temperature at which moist air condenses into water droplets, see figure 2. Every time we breathe out, moisture follows, breathing on a cold mirror and it becomes obvious, and the same applies to bees. When bees burn sugars, large amounts of water are created, where 1 kg of honey gives rise to approximately 600 gr of water (3) which the bees must somehow manage. In an uninsulated hive, the moisture will condense on the surface that is below the dew point, which means that if the roof is poorly insulated, the risk of condensation increases, whereby the water droplets run down onto the bees and cool them, figure 2.

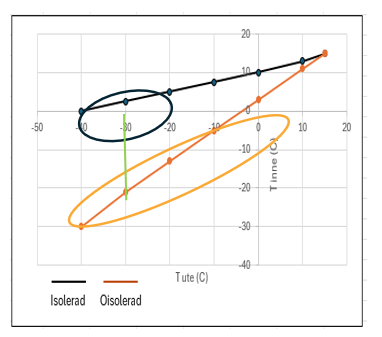

If we increase ventilation, the bees have to produce more heat, which creates more moisture with an increased need for ventilation, and so on. When the ambient temperature has reached -10 degree C, the bees cannot shrink the cluster any more – they can only increase heat production (4). Although the bees can increase their metabolism and briefly produce large amounts of heat, this is extremely stressful for the individual bee and wears them out prematurely, see Figure 3.

Heat output from a bee, right image. Above 18 degree C only 1-2 mW/bee (resting metabolism). At 10 degree C the output has increased to 12 mW which strains the bees and shortens their lifespan. (Graph from Myerscough (2)).

Insulated hive and R value

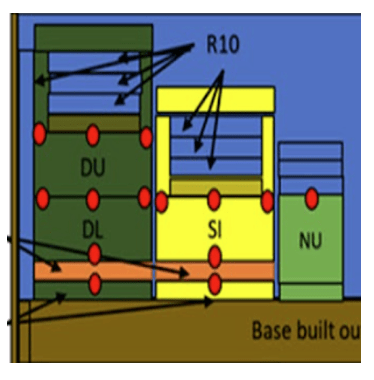

By insulating the hive, we can help the bees avoid being in tight clusters, which provides two advantages: firstly, the bees will use less honey, which reduces the amount of moisture, and secondly, it reduces the risk of condensation because we avoid cold surfaces that can reach the dew point. Then the question arises of how best to insulate the hive, where we can take the natural bee habitat as a starting point, Figure 4. The bees chose living trees with an entrance hole a little way up in the tree trunk where the R value upwards is “infinite” because there are several meters of wood and enormous mass that acts as an energy reservoir. The walls are approximately 15-20 cm thick, which gives an R value of about 10.

R value is the thermal resistance of a material layer, larger R=> greater resistance, right image.

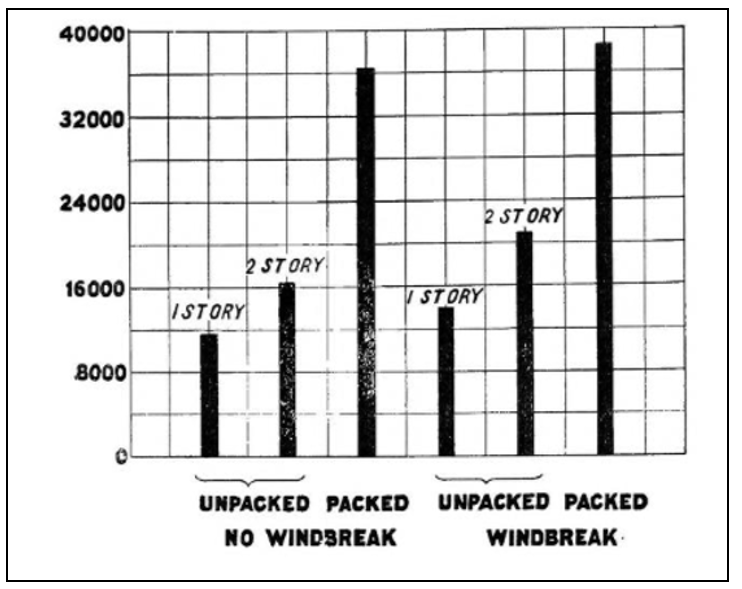

If we transfer the above to a beehive, we need to get up to R=10 on the sides, which corresponds to 50 mm of foam plastic or 200 mm of wood. Upwards, R=30 is needed, which corresponds to 150 mm of foam plastic, see figure 5. Measurements show that the bees in a well-insulated hive maintain the temperature closest to the cluster at 6 degree C even if the outside temperature is -30 degree C, which means that the bees sit in a loose cluster and can move freely in the upper part of the hive. The honey layer is kept warm and acts as an energy reservoir, which evens out short-term cold snaps. The result is that the bees come out stronger in the spring, figure 6, and are ready for the first forage. Of course, the need for insulation is greater the colder the winters, but good insulation during the winter will generally help the bees come out stronger in the spring, see figure 6.

Images from: http://www.northof60beekeeping.com

Referenser.

1. Simpson, J (1961) Nest climate regulation in honey bee colonies. Science 133 (3461): 1327-1333

2. Myerscough, 1993. A Simple Model for Temperature Regulation in Honeybee Swarms

3. Randy Oliver, 2020. Scientific beekeeping: Part 7A-C, 14

4. OWENS 1972, THE THERMOLOGY OF WINTERING HONEY BEE COLONIES

5. http://www.northof60beekeeping.com